Finding the Bifröst Station

Despite the efforts that precipitated the Second Orbital War, American interest in a Martian colony soon waned. Business leaders were content with the near-exclusive American domination of Luna, which turned a sizeable profit as Earth’s primary refueling station.

Back on Earth, massive engineering projects had artificially stabilized the climate, returning weather and temperature patterns to those of the mid-19th century. The nations of Earth breathed a collective sigh of relief, feeling a newfound sense of control over the disasters that had plagued them for centuries. For a brief few years, terrestrial powers – and the United States in particular – focused more on their newfound success than their lust for space exploration.

THE QUEST FOR COLONIES

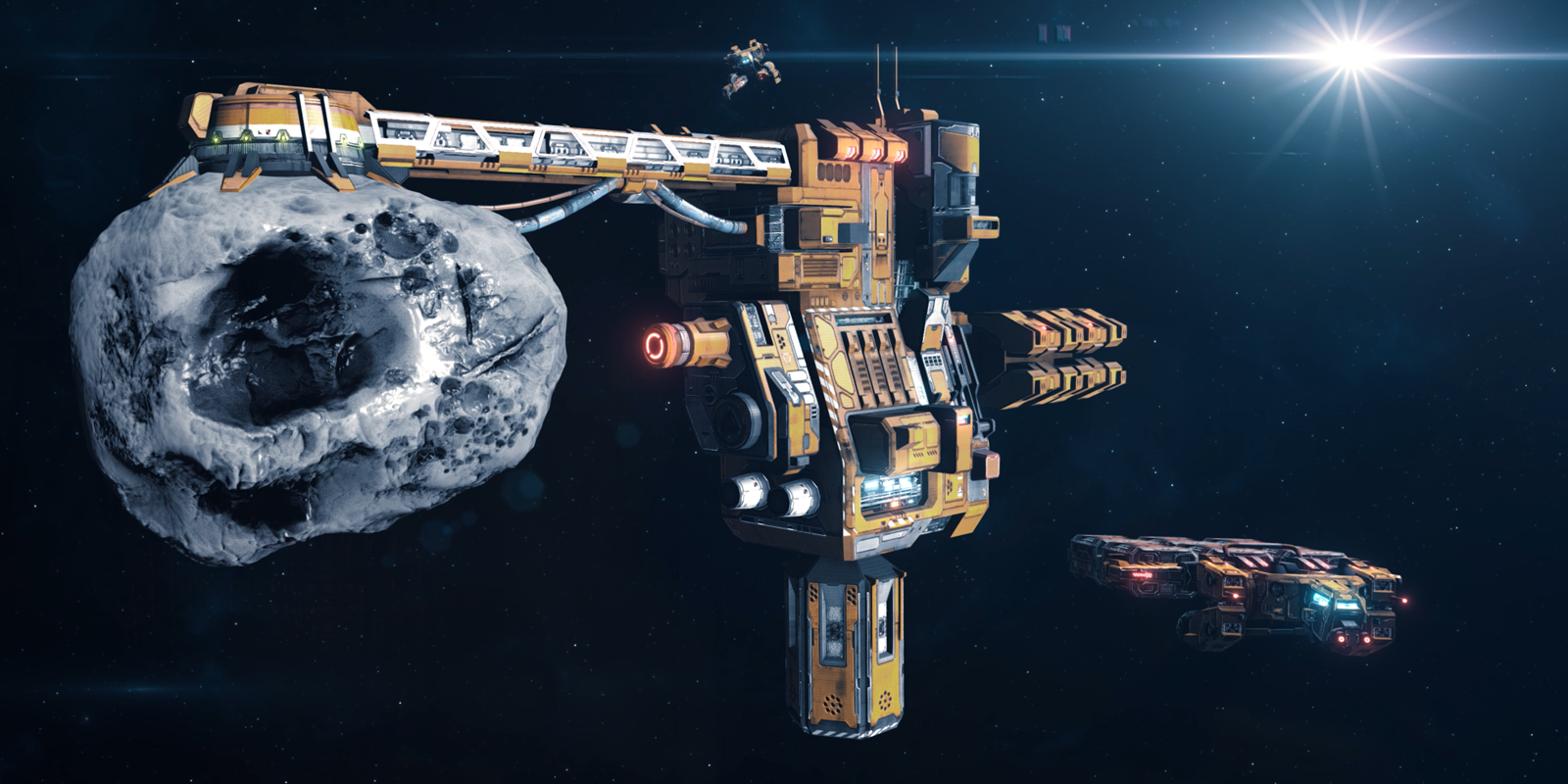

This rest did not last long. By the late 2150’s, a Russian claim on Ceres quickly proved immensely profitable and began to shift the balance of power once again. European colonists were similarly beginning to dominate Europa and Ganymede, while Chinese engineers celebrated the success of the colossal Jinxing Platform over Venus.

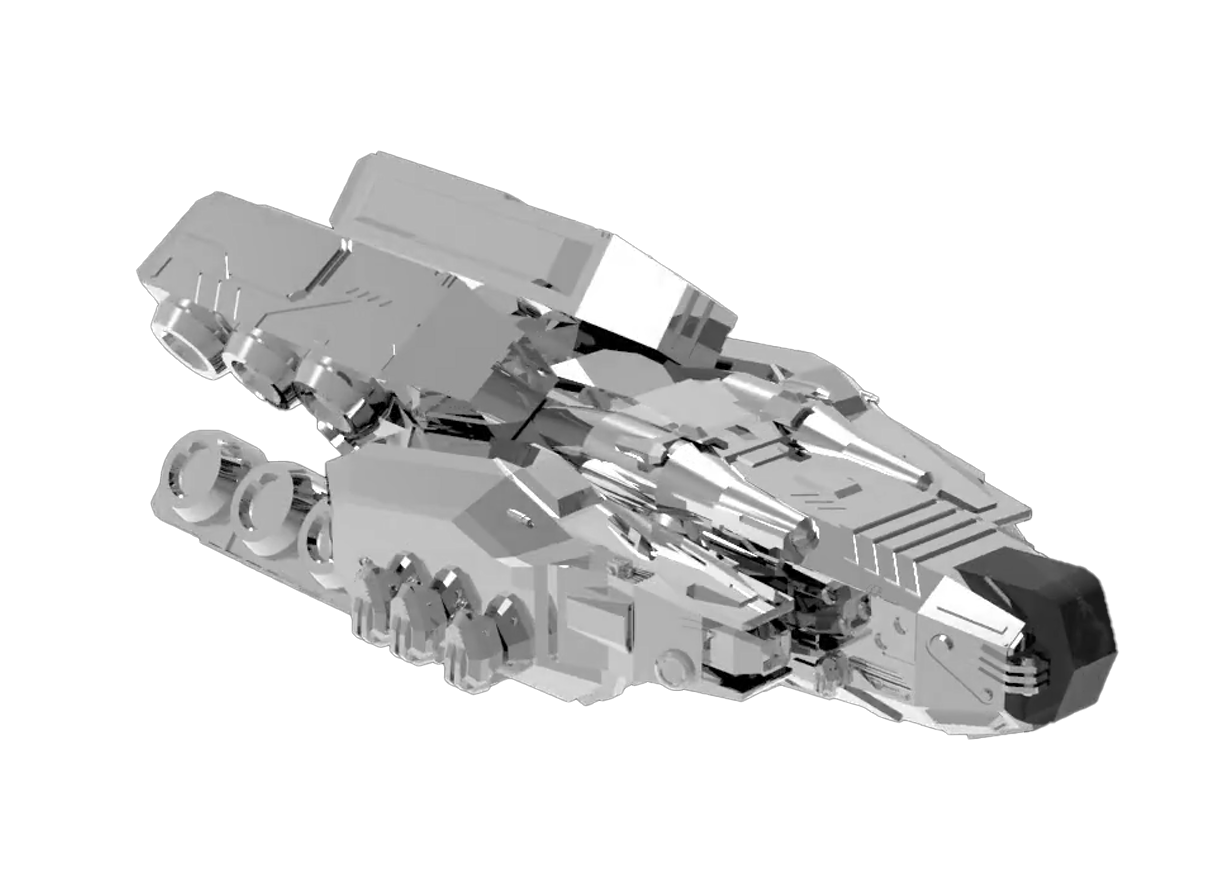

American interest in colonization was forcibly rekindled, and another effort to explore and colonize began. American fleets – funded by the Windfall Corporation – soon established twin colonies on Titan and Enceladus, two of the moons of Saturn.

Despite the lull in public interest, Windfall engineers had not been complacent. Through the late 2140’s and 2150’, they quietly focused on new iterations of older ideas – despite the political battles that raged against them. Out of several black projects, there was one standout success in 2145. In that year, Windfall tested the first ship using a variant on the original NearGrav system, which eliminated the need for ships to carry reaction mass for primary propulsion. By projecting a gravitational field in front of the ship, the vessel would effectively fall toward the ever-moving force, generating tremendous acceleration. These new “gravity drives” allowed ships to accelerate at a constant rate up to a new safety limit.

While it made little difference for short runs between planets and their moons, the technology would make travel to the farther reaches of the solar system possible like never before. An early press release described the new design as “pulling humanity up by our bootstraps” and the nickname “bootstrap drive” famously stuck.

THE FINDING OF THE UPOS

As humanity began a renewed effort to race across the solar system, a nagging question prevailed: Was humanity alone in the cosmos?

In thousands of scientific and colonial expeditions, only a few ambiguous microbial fossils on Europa had ever hinted at anything resembling extra-terrestrial life. Most scientists admitted that statistics alone demanded the presence of non-terrestrial life somewhere in the cosmos, but no human expedition ever returned with signs of it. International and interplanetary organizations rose and fell in attempts to contact non-human intelligence. Much as it had since the 20th Century, the Fermi Paradox baffled scholars well into the 22nd century.

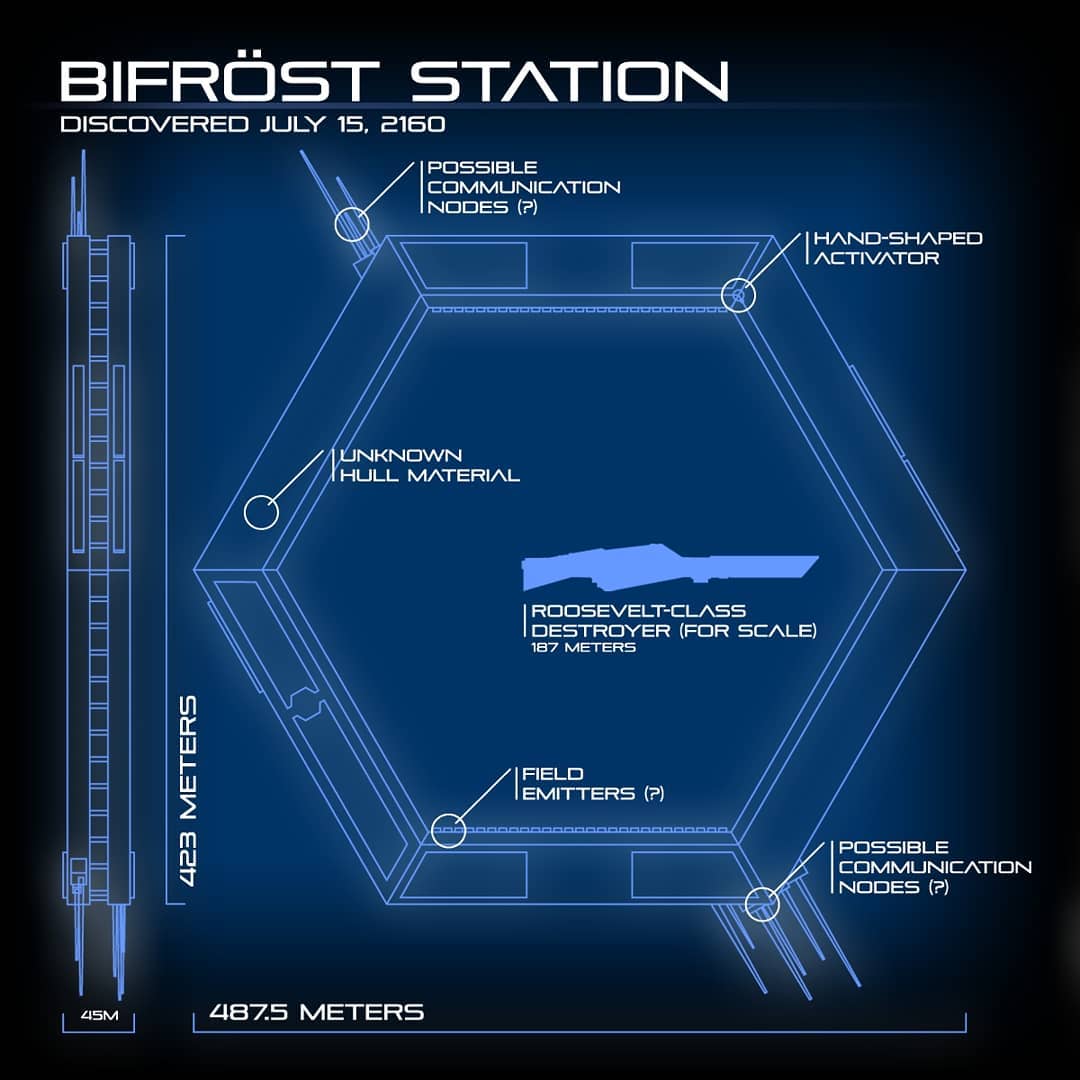

The discovery of 2160, then, came as a remarkable surprise. In that year, a European scouting ship — The Éclaireur – began an expedition beyond the Oort Cloud. Amidst a large cluster of ice and debris, the crew of Éclaireur discovered a massive object nearly 500 meters across. Arranged as a perfect hexagonal ring, the object was undoubtedly unnatural. Built from an unknown metal, the surface of the object was perfectly pristine – except for a minor imperfection only 25cm wide in one of the hexagon’s joints. Upon closer discovery, the crew was able to observe that the object’s imperfection was an indentation in a familiar shape: a human hand.

News of the object’s discovery was an instant sensation. The topic of the structure – known as the Unidentified Post-Oort Structure (UPOS) – instantly consumed humanity’s attention. While the crew of the Éclaireur continued to study the object, non-European nations began to ready teams of scientists to investigate the object on their own.

ACTIVATING THE STATION

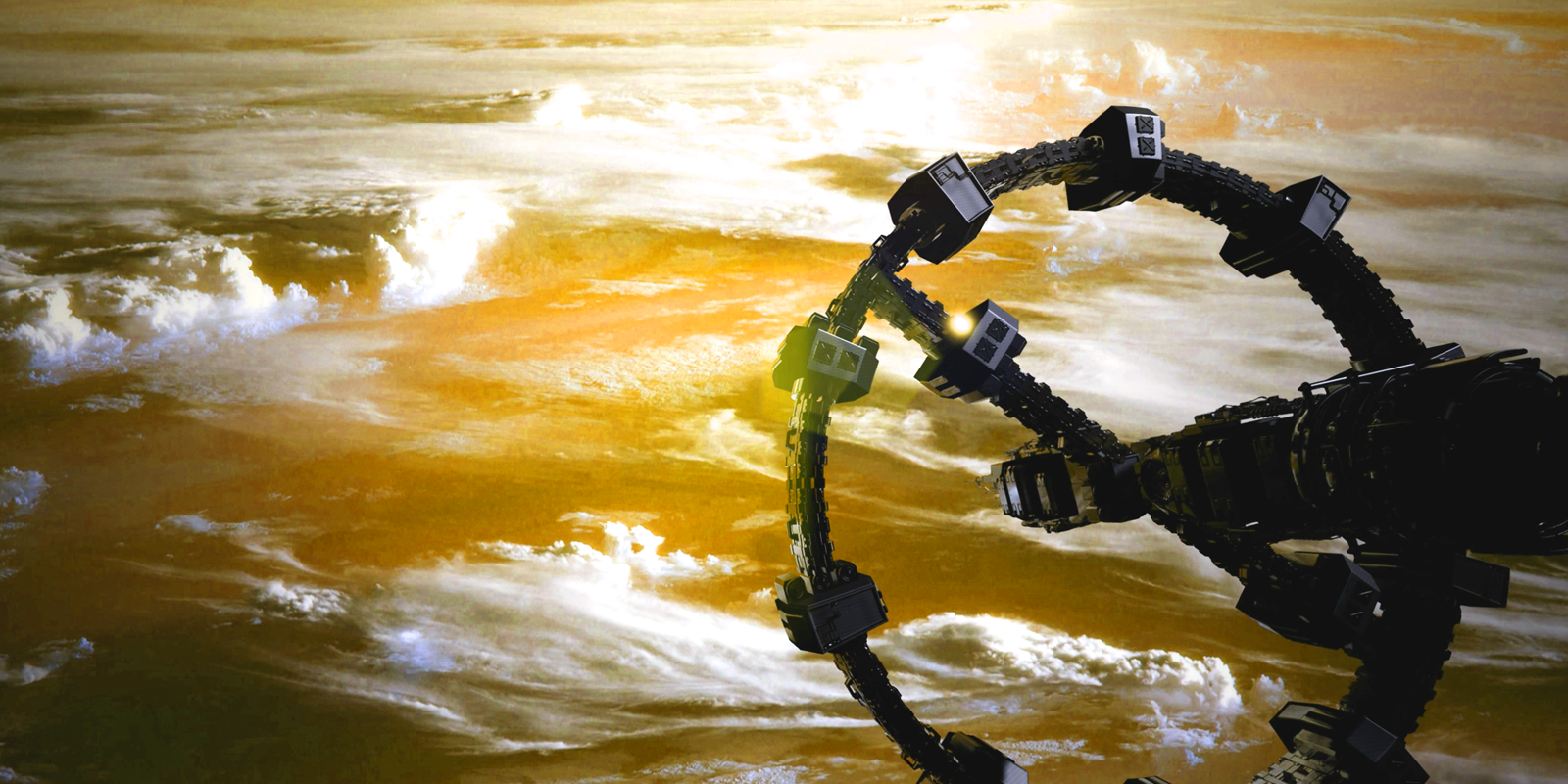

On July 18, 2160 – three days after the structure’s discovery — the UPOS proved even more wondrous. Establishing an atmospheric seal against the structure’s hull, the Éclaireur’s crew was able to investigate the imperfection site more fully. When one of the researchers placed his hand into the indentation, the object sprang to life. Observers noted the activation of “a thousand lights” across the hull of the UPOS while a mechanical hum began to sound from deep within.

Outside the Éclaireur, a manned probe passing through the center opening of the UPOS suddenly vanished, baffling and terrifying the members of the team. A short time later, though, the probe — manned by astrophysicist Louis Chenier – quickly reappeared.

Chenier was ecstatic, claiming that he had instantaneously passed into a completely different region of the galaxy. Though the sensors on his vessel were limited, he was quickly able to tell that the station had transported him beyond the Sol system and into the orbit of another star, complete with its own set of planets, planetoids, and moons. He had returned by flying through the center of another UPOS, though Chenier declared it was possible he had flown again through the original object

“Incroyable. Absolument incroyable…”

LOUIS CENIER – European Astrophysicist,

upon returning through the Bifr

öst Station

ACTIVATING THE STATION

As the scientific teams of other powers raced toward the UPOS, the Éclaireur team continued their research. Noting the object required no further activation, the entire ship passed through the ring and into the unknown. With copious and diligent sensor readings, Éclaireur’s crew ascertained that their destination was located somewhere in the Milky Way’s Perseus Arm, tens of thousands of light years from humanity’s sun. Though the Éclaireur hesitated to venture far from the station that had brought them there, deep scans into the system discovered the presence of seven planets and twenty-three planetoids – many of them rich in minerals.

Most importantly, though, was the data surrounding the system’s second planet from the star. With a stable orbit and an atmosphere rich in oxygen and nitrogen, the researchers were convinced the planet would be an easy target for human terraforming. This hypothesis was only validated when further scans indicated the presence of both liquid and frozen water and a gravitational pull almost identical to Earth’s.

Returning through the UPOS to report their findings, the Éclaireur crew became instantly famous. News outlets praised the crew’s heroism while governments began to discuss their own responses. In common reference, the UPOS began to be referred to as the “Bifröst Station,” a nod to the mythical bridge between worlds within Norse mythology.

For a brief moment, humanity stood united in a new hope and vision for the future. The Bifröst Station offered a new and seemingly-limitless potential for mankind to reach into the unknown vastness of space and break the boundaries of its own star system.

Yet just as quickly, the serenity was shattered by the realization of the station’s strategic and economic advantage. Even as they drew close, governments began to recall their science teams. In their stead, well-armed warships raced to take hold of the discovery.